Vassilis Benopoulos

Influence: a two-way street

The interaction of fact and fiction in intelligence is too often dismissed as fiction. The two worlds are too often seen as existing in parallel, with fiction offering extravagant or stretched accounts of a secret world unencumbered by such narratives. The reality of the situation is more interesting. Literature and the Intelligence World have influenced each other in fruitful and concrete ways, and this interaction has been as influential to the Intelligence World as it has been to Literature.

On the one hand, Literature has quite clearly drawn from real events, operations and individuals. More importantly, writers in intelligence have used their personal experience of the Intelligence World to inform their work, to create an atmosphere, and to construct their fictional stories. Ian Fleming joined Naval Intelligence in 1939, working closely with its Director in a number of covert operations throughout the Second World War, most notably Operation Mincemeat. Fleming’s direct experience with intelligence networks, subversive activities and war technology (Enigma, special devices, gadgets etc) gave him endless material for his later career as author of the James Bond books. Similarly, it is a well-known fact that David Cornwell (John le Carré) joined the MI5 in 1958, running agents and conducting interrogations before being transferred to MI6, where he did covert work in Germany until 1964. Cornwell’s own experience of the Services, although limited and fragmental, nevertheless informed his books; details of atmosphere and esprit de corps as well as themes of secrecy and betrayal can be linked to Cornwell’s understanding of the Services. It has been suggested that the prototype for George Smiley was Maurice Oldfield, Chief of SIS from 1973 to 1978. Additionally, anyone who has read Tinker, Tailor, Soldier, Spy (1974) will not fail to draw parallels between Bill Haydon, the charming Oxford-trained traitor, and Kim Philby, the charming Cambridge-trained traitor who wrought havoc on SIS in the 1960s.

On the other hand, the Intelligence World has equally drawn from the creativity and imagination of the Literature to inspire operations, to form strategies and to construct processes. In 1941, FDR sent Colonel William Donovan on a European trip, particularly aimed at collecting lessons for building an American intelligence service, and for enhancing cooperation with the SIS. The information gathered helped to eventually found the Office of Strategic Services which later became the CIA. During his trip to London, Donovan was connected to Ian Fleming. A memo sent by Fleming to Donovan on June 27, 1941, begins thus: ‘I have prepared a few notes on some steps which will have to be taken in order that your organisation can be set up in time.’ The three-page memo contains a range of suggestions concerning staffing, organisation and administration. Fleming throws in ideas about sabotage, counter-espionage and cajolery of other departments in order to set up a successful Service. It appears then, that although the author of Bond did not create the CIA, he was definitely one of its godfathers. Allen Dulles, the first civilian Director of the CIA, was also a great admirer of spy novels, and later served as the prototype for Felix Lighter, Bond’s American counterpart. Allen Dulles had read Rudyard Kipling’s Kim (1901) when he was a young diplomat and kept a copy of the book with him throughout his life. The excitement contained in Kipling’s pages infused his imagination and appetite for covert action. In helping create and later run the CIA, Allen Dulles ignited an era of covert subversive action, leading to military coups in Iran and Guatemala in the early 1950s. Dulles also advocated for increased spending for technological innovation, downright urging CIA quartermasters to try and reproduce Bond gadgets.

The above examples are only indicative of a broader pattern. What is clear is that we must not belittle the two-way interaction between Literature and the Intelligence World. As it happens, art imitates life, which imitates art.

Vassilis Benopoulos

Kings College London

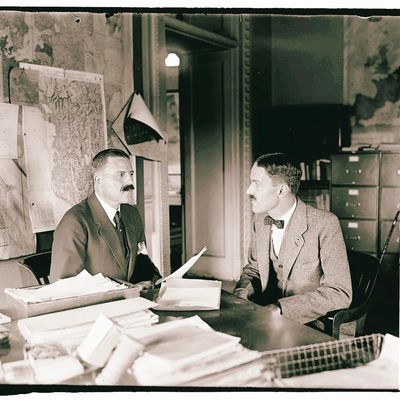

Allen Dulles with Peter Jay

National Photo Company Collection, Public domain, via Wikimedia Commons

Powered by GoDaddy