A tough Bond to break? The enduring allure of drawing fiction into discussions of the secret state

Dr Huw Dylan

Kings College London

Openness has long been a fraught issue for the British secret state. Austin Chamberlain once noted in parliament that you could not discuss matters of secret service because, once you did, you no longer had a secret service and would have to do without one. Mansfield Cumming, the first ‘C’, Chief of the foreign branch of the Secret Service Bureau, reportedly used to joke with his staff that he looked forward to publishing his autobiography after retiring: 400 pages… each one blank. He never did retire. He died in post. (Survived, of course, by his diaries, which, decades later, were written up by Alan Judd, and published as an account of the early years of the foreign intelligence service.) But secrecy has characterised the secret state since its inception. It has, however, never been absolute, nor has the imperative to keep schtum been applied with absolute consistency. One of Cumming’s officers, Compton Mackenzie, famously wrote of his adventures in ‘Greek Memories’, and was prosecuted for his troubles. Others, often more senior, and as noted in Moran’s fascinating study of Secrecy in the UK, ‘Classified’, frequently got away with telling their stories. Notably J. C. Masterman, who published is book ‘The Double Cross System’, and the story of deception in the Second World War, in 1972, to much fascination and with no subsequent knock on the door. The foreign secretary, Alec Douglas Holme, apparently saw to that. Since then, the intelligence world has emerged from the cold, slowly and carefully.

More recently the services have become more open than ever, partly through policy and choice, partly because certain developments have thrust it upon them. The British services have been brought in from the cold legally; they are now regulated by a number of acts of Parliament. They have opened their recruitment practices, relying less on the ‘old boy’ network and diversifying their workforce. Many intelligence papers are now openly accessible in the archives; historians frequently investigate history that not that long ago would have been withheld from the public record. But operating in secret in the digital world has become harder; officers run a higher risk of exposure than previously. And digital data can be leaked en masse, revealing significant swathes of the secret state in fell swoops, as occurred with Edward Snowden. A steady stream of information about intelligence services is now available. And yet the day-to-day work, revealed in quite vivid detail in many accounts – notably the ISC’s investigations into terrorist attacks, or the supporting material published to inform the debate concerning the 2016 Investigatory Powers Act – competes for space with fictional representations of British intelligence, and the shadow cast by Ian Fleming’s James Bond.

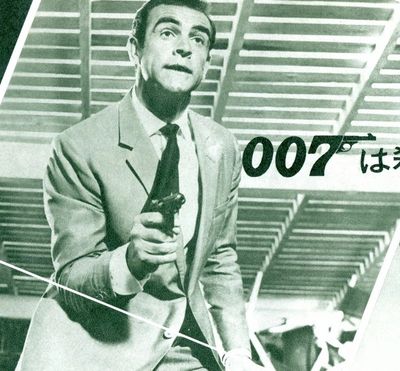

Several scholars have examined the enduring legacy of Bond. The fictional antics of 007, and particularly the tools prepared for him by Q-Branch, have inspired many governments to create analogue gadgets to deploy in real life. And the intrusion of Bond into the public discussion of intelligence work shows little sign of waning. The recent speech by the current ‘C’, Richard Moore, illustrated this. In a discussion of what he saw as the paradox in which his Service existed today, needing to be more open to remain secret, he refers to the challenge of developing the hi-tech gadgets that facilitate espionage through the lens of Bond. ‘Unlike Q in the Bond movies, we cannot do it all in-house’, he noted. Quite so. And he is by no means the first senior SIS officer to integrate Bond into discussion of their work. Sir Colin McColl is said to have once noted that Bond was the best recruiting sergeant in the world.[1] More recently, Moore’s predecessor, Alex Younger, reflected on some of the more problematic elements of having his service’s brand be defined in the public consciousness, in some respects, by a fictional character. On the plus side, he noted, it was a powerful alure, people were intrigued, you had a brand; one the other, brand Bond gives people a completely false idea of the qualities that make a good SIS officer.[2] Indeed, Bond is in many respects antithetical to many of the values that the more public services espouse: regulation by law, respect for human rights, team-work and communication, diversity, subtlety – all stressed by Moore in his recent speech. Perhaps as the momentum toward openness continues fact will eventually nudge fiction further to the side-lines when people think of the Secret Intelligence Service. And, should that be the case, the Services and their staff will doubtless be more diverse organisations, and stronger for it. But, in that scenario, perhaps future officers will look back with a degree of nostalgia at the extra bit of cache that their predecessors felt they enjoyed when going about their secret business in some quarters through being associated with the relatively absurd antics of a fictional spy who gave British intelligence the sheen of Hollywood glamour.

[1] This claim is widely references, see, for instance https://warwick.ac.uk/newsandevents/pressreleases/the_spies_who/

[2] See the discussion reported here, https://www.theguardian.com/books/2019/may/30/james-bond-still-a-strong-recruitment-sergeant-for-mi6-says-expert

Powered by GoDaddy